Concussions: A History

For decades, many athletes and their trainers alike looked at concussions as little more than a nuisance thanks to the quiet nature of the injury: whereas a torn tendon or broken bone would physically prevent a player from performing at their highest capacity, keeping them off the field out of necessity, the wide-ranging symptoms that repeated head trauma caused were harder to quantify and thus, easier to ignore.

These days, thankfully, concussion research is progressing faster than it ever has before, with athletes, coaches, and medical personnel alike all acutely aware of the dangers that traumatic brain injuries can cause, including diseases like Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE). With that said, there’s still a way to go before our knowledge of concussions reaches a level that is truly safe. We still don’t know just how much brain trauma is too much, how many hits to the head (or what level of force) contributes to irreparable damage.

While steps have been taken to protect players who suffer from these injuries, the macho culture that is intrinsic to collision sports means that athletes won’t always do what’s best for them, even if it could mean they’re ruining their future quality of life.

Concussion Protocols: Where We Stand Today

While it still isn’t perfect, the NFL has carefully defined concussion protocols that each team must adhere to if an athlete is suspected of having a concussion. Even if immediate tests don’t reveal the occurrence of a brain injury, players still must take time off to work their way through the protocol, with the various requirements they must adhere to designed to thoroughly test for concussions.

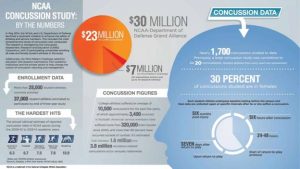

College football lagsbehindthe NFL, though. While the NCAA does serve as an overarching governing body in the sport, they leave the question of concussion monitoring up to each individual league (and thus, each program). Leaving teams up to their own devices when it comes to policing these devastating injuries puts student-athletes at risk: the NCAA brought in more than $1.1 billion in revenue in 2022, which makes their refusal to commit to the health of the student-athletes who make them rich by putting their bodies and futures on the line even more disappointing.

When it comes to individual school protocols, the University of Louisville, for instance, takes “a multi-faceted approach to treating concussion that includes educating all student-athletes, coaching staff, and strength/conditioning personnel. It also delineates the role of the members of the Sports Medicine staff as well as baseline testing for those who participate in sports at risk for concussion.” Cardinals’ fans saw this play out during the 2022 season, when Louisville quarterback Malik Cunningham went down with a concussion against Boston College, missing the better part of a month as he worked his way back from the injury.On a side note, speaking of Louisville, the state of Kentucky is set to legalize online sports betting in the upcoming months. If you are a Cardinals fan you can take advantage of DraftKings Kentucky if you’re looking to support your team and get in the action.

Under Pressure: Inside the Workings of a Multi-Billion Dollar Industry

It can take time for an athlete to realize they’ve just suffered a concussion, whether they’re dazed from the blow they sustained or still operating on an adrenaline high that numbs the sting of a blow. To counteract this, NFL teams hire independent spotters to keep an eye on what’s happening on the field (as do many college programs and leagues), looking for potential signs of traumatic brain injuries among players during and after each play as an added level of safety.

To make matters worse, the invisible nature of concussions brings an ugly dose of subjectivity to the question of diagnosis. If a player wants to get back on the field, putting their health and safety at risk out of a misguided desire to help their team or preserve their chance at playing time, they can lie to or put pressure on team doctors in an attempt to expedite their return before they’re fully healed: it’s difficult to determine what a player is dealing with objectively when there’s no broken bone or shredded ligament to visually diagnose. Of course, it isn’t fair to blame the players in these situations, as they could be dealing with peer pressure from teammates and coaches alike to rush their recovery.

College players don’t receive guaranteed money (if they manage to make anything at all) as the pros do, so they’re under added pressure to rush a return: the best ability is availability, and no one is winning the eyes of an NFL team by riding the bench. Per the CDC, healing from concussions isn’t a linear process either as mild concussions can take an athlete longer to recover from than a severe head injury can: everyone is different, and the muddied waters make the situation difficult to gauge for athletes and doctors alike.

Medical personnel take steps to account for this, as the aforementioned baseline cognitive testing gives them an idea of how fast or slow a person responds to the questions used to test for concussions when healthy, making it easier to gauge the change in behavior after a head injury.